On Chocolate and Grief

In memory of Evan Knight Martin

Mid October last, I sighed and pouted at my partner, Trevor, saying “Something feels off today. I don’t know why, but I just feel like I should be at home.” We were in Los Angeles for an event with his extended family, and we had arrived a couple of days early to explore, filling our days with food, window shopping, long walks in beautiful places, and (of course) chocolate tasting. But during those days, I often felt out-of-sorts. I had trouble focusing on what we were doing and woke up from sleep feeling unrested.

It was only later that I wondered if what I felt was actually a sense of foreboding.

October 16, 2010, began as a day of celebration. We shared a delicious lunch with Trevor’s parents, stopped by a chocolate shop and chatted with the chocolatier and staff, then joined his family at the event. At one point, I joked with Trevor and had the sudden thought that the joke sounded exactly like something my brother might have said. I chuckled to myself, as I often have, at the recognition of our similar sense of humor.

Afterwards, Trevor and I piled into our rental car to head to the second location of the evening. We shared a few of the truffles we had picked up that afternoon. Just as we were about to drive off, a cell phone rang — my father was calling. I answered, and he said in a voice filled with emotion, “Hey Carla, it’s your dad. Are you somewhere where you can sit down and talk? I’ve got some really bad news for you.” As he spoke, telling me that my brother, Evan, had died only hours before, my breath quickened, and then I held it, I don’t know for how long.

Evan was twenty-five years old and his heart had stopped, immediately and without warning. Just like that, he was gone.

Within a matter of hours, Trevor spirited us back to Boston, and then we jumped into action to notify our friends and family of the loss. The next several days were among the most emotionally powerful that I have ever experienced. For two weeks, we woke early in the morning and drove to my parents’ home, then spent the day hosting an endless stream of bereaved guests, planning the wake and funeral, writing the obituary and eulogies, scanning hundreds of photos, answering phone calls, texts, and emails, trying to make some sense of the new world. We were in shock; our emotions went up and down like a rollercoaster ride. But even when I think back on the darkest moments of those weeks, I remember the almost euphoric, peaceful feeling brought on by the kindness displayed by others to our family. I smile when I recall the image of my mother’s best friend bursting through the kitchen door, her face contorted with worry. She held a giant Ghirardelli dark chocolate bar out in front of her — an offering. “I couldn’t think of anything else worth eating in this situation,” she said, wrapping us up in her arms.

At the end of those long days filled with tears and laughter, Trevor would drive us home to our apartment in the city. The lights along the ocean twinkled in the dark blue night, and I would breathe deeply for the first time in hours as we crested the exit ramp from I93 to I90, flying high above the the city for a few special seconds. I spent the rest of the ride doubled over in grief stricken agony, silently sobbing as the reality of the loss began to hit me.

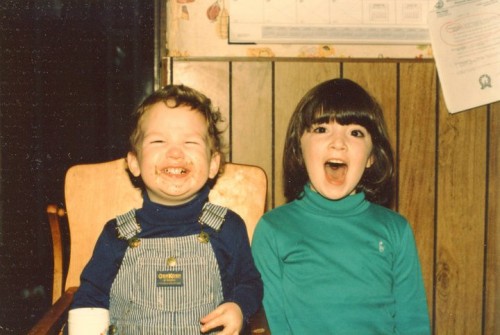

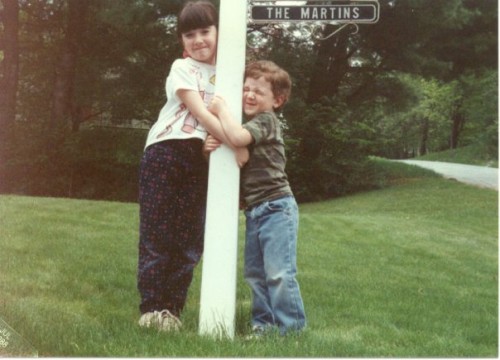

My brother was a remarkable person. Though he was technically my *baby brother-little brother-three and a half years younger than me, so I used to babysit him and boss him around brother,* as we both got older, the age difference melted away. He excelled at brotherly activities, whispered tongue-in-cheek threats to my boyfriends over the years, helped me to find and buy my first (used) car, then took it upon himself to give it regular thorough inspections and tune ups. We shared many things, including a sweet tooth. Starting at a young age, he snuck and hoarded the chocolate treats that he knew I loved and that our parents mostly forbid, getting as much pleasure from sharing them with me as he did from eating them himself.

For my part, I was thoroughly smitten with sisterly brother-hero worship. I loved doing Evan impressions for my friends, acting out his latest hilarious stories and antics, insisting that it was just a matter of time until he would be discovered and make a splash as a TV personality. “You have a car? You have to take it to my brother. His hands are magical. He can fix absolutely anything. He is a genius — a car whisperer!” I would boast. We spoke regularly, texted often, traveled together, offered one another advice on life and love, and dreamed out loud always. He was, in so many ways, my closest and oldest friend.

Evan’s special spark lit up a room and his way with words never failed to elicit a hearty guffaw. Just a week before he died, he had a room full of relatives in stitches as he left a wacky voicemail message for a cousin. He was creative, hilarious, obsessive about his interests, empathic, delightful.

Hundreds of people attended his wake. Even the staff from the pet store where he bought fish food sent flowers. A large group of his friends, bandana-clad in his signature style, organized a motorcyle procession to and from his funeral, revving their engines as they passed quaint colonial New England homes. They continued this tribute with a series of beautiful tattoos, parties in his honor, and a year of embracing his family as their own. Evan would have absolutely loved it.

Despite Trevor’s valiant efforts to feed me, I was mostly unable to eat for those first two weeks following Evan’s death. I lost a startling amount of weight, though I only felt weak kneed once, at the wake, while greeting and thanking the hours-long stream of people who came to bid my brother goodbye. My aunt, ever at the ready, snuck me a couple of Lindt truffles that she had stashed in her purse. Those tiny, half melted candies gave me the boost I needed to make it through the night standing. After that, my immune system buckled, and I caught a miserable cold. On the day of the funeral, I was quite literally speechless, having lost my voice to a cough that would linger for weeks. I found the forced silence oddly comforting, and sat at the edge of my parent’s living room, holding onto a series of thoughtfully offered hands and watching the people from all parts of our lives talk with and comfort one another. A slideshow of pictures of my brother played on an endless loop in the background.

I developed a complicated relationship with my own heart, which, because I was a first-degree family member of the deceased, needed to be studied, recorded, ultrasounded, MRIed, analyzed to make sure that it was healthy. I wondered to my heart, Can I trust you to keep beating? There were days when I curled up with sorrow and I wondered to myself, Could I be so heartsick with sadness that my heart would stop beating? The doctors tell me that my heart is OK. I believe them, mostly.

Major credit card companies have an automated system to handle the reporting of a death. There’s no human voice with a consoling message. Just a computerized robot instructing “press 1″ for this, “press 2″ for that. I dutifully pressed the numbers when I cancelled my brother’s credit card accounts, eventually laughing at the cruel absurdity of the situation. It took months and mounds of paperwork to get autopsy results, to cancel recurring payments, to resolve his estate. There were bureaucratic road blocks and corporate dishonesties all along the way. These things have resolved with time. The fact remains that there are many parts of our society that are cold and unfeeling.

In the year of magical thinking that followed Evan’s death, I was lucky — I got good advice from loved ones. Lean into the pain, they said. Then concentrate on navigating the new world. I tried to spend my time with family and doing things that reminded me of happiness. I handmade holiday gifts, cooked and baked for even the tiniest of occasions, cleaned and rearranged my home, read dozens of trashy fantasy novels filled with exaggerated emotions and caricatured personalities. But the grief was so intoxicating — I could almost taste it, smell it — I started to fear for the parts of myself that were harder to remember. I often found myself unable to work on anything but the most mundane tasks. Unable to reach out to anyone but the most sympathetic friends. What do I like to do? What did I like to do? I puzzled.

Loss like this is so intensely personal that it can amount to a felt loss of identity. I often questioned, Who am I without Evan? All of my fondest childhood memories involve my brother. Did I know how to be an only child? Could I handle our parents, who we both adored, without my brother to share in the understanding of how their particular version of parent-crazy both works and baffles? I spent hours, then days working out possible solutions to every situation that arose in the lives of my loved ones. How can I fix things? What can I do? Even moments after learning about his death, I remember asking my parents, “What can I do?”

Grief brought me terrifying moments of insecurity, feelings of inadequacy and profound isolation, the occasional sense of being irrevocably lost. It came in waves; it often shocked and surprised me. I longed for Evan, was furious at fate for having cheated him of time, was heartbroken for our family and his beloved partner, Kristie, who lost the dreams of a future that they would create together. I couldn’t bear the thought of losing anyone else in my life. Most of all, I wanted Evan back. I wanted to bask in the warm sense of belonging that he provided. I wrapped myself in a thick cloak of nostalgia. I wrapped myself in a thick fleece blanket and curled up in a corner of my couch.

During that cold descent into winter, we all developed a certain appreciation for the intangible, remembering signs that had indicated he might be leaving us, or noticing signs that indicated he was still present in his way, still loving us. Our last conversation, just days before he was gone, was suddenly as much precious memory as prophecy. “I saw the cutest kittens at the shelter, Carla,” he had hinted, knowing how much I loved his own two precious cats. “Just go pick ‘em up! They need a good home.” In January, four months after his death, I started volunteering to help with cat adoptions at the shelter. By May, seven months after, two lovely lady cats had joined Trevor and me in our home.

Eventually, there was comfort to be found in food. Grilled cheese, mac and cheese, mashed potatoes, stuffing, pasta, cookies, pie, ice cream… and chocolate. Lots and lots of chocolate. Fifteen pounds worth on the thighs and hips, to be exact. Because there are times when there are more important things than fitting into your jeans.

The grief, with the food, was all consuming and powerfully narcotic. For a time, I avoided certain places, thinking I could prevent the sting of awkward social interactions. Some people said nothing about my loss but made sad eyes across rooms; others said things that were completely insane. (I considered, on multiple occasions, handing out a list of inappropriate things to say to a bereaved person, real quotes from people I know, but ultimately decided it wasn’t worth it to burn bridges just for some raucous comedy.) I was actively lonely, because the halls of graduate schools can often be deserted and devoid of emotional connection, and because I felt that few people could understand the depth of my pain.

I am young enough that most people my age have not lived through a loss like this. Our society tells us that young people rarely die. That showing others our sadness might inconvenience or upset them. But my youth often feels like nothing, meaningless, it having been robbed from my brother in the blink of an eye. And my emotions are always close to the surface, nearly impossible to hide. I have come to understand that others’ confusing behavior stems from a lack of experience rather than a lack of compassion. I am learning to express my love and gratitude to everyone, regardless.

Thankfully, Evan and I shared a spring in our step, a twinkle in our eye — one of the many gifts from our quirky, dreamer parents. I eventually decided that, in the interest of survival, it was time to reignite that spark. So, a few months after his death, I started signing up for small things, doable things. Things where no one would be hurt or inconvenienced if I bailed. I gave a talk at an important conference to try and get back into the swing of performing my academic life. It completely exhausted me, but it went well. I went back to planning dinner parties and activities with friends, something that I had previously relished the opportunity to do, but had stopped altogether because I had never known if I would feel like putting on pants from day to day. Pajamas were soft and comfortable and safe. Clothing brought me back into my community.

And I finally started sharing my research on chocolate, a project that my brother had long encouraged. “Everyone has a thing, Carla. You should go with it.”

In the past year, I have learned a great deal about friendship and compassion, about mortality and the impermanence of life. But even these lessons don’t lighten the heavy weight of his absence. Evan is gone and that’s wrong.

However, it is thanks to the community surrounding this blog that I have started to thrive again. With each blog post, meeting, email, or friendly tweet, I gain a bit more momentum.

This Sunday marks the one year anniversary of Evan’s death. Today marks the eight month anniversary of Bittersweet Notes. In these eight months, I have shared in chocolate adventure and travel with dozens of people. I have made new friends, some of whom I’ve met in person, others whom I hope to meet in the future. I have been the recipient of countless messages of encouragement. I have learned so, so much. As with other challenges in life, this one in some ways the most difficult of all to accept, it is learning and sharing, connecting wholeheartedly with other people, that is guiding me back to happiness.

A year of arrhythmic chaos. Life eventually falls back into a steady tempo. I watch the sun rise and the sun set, I pet my darling kitty ladies, I share chocolate with Trevor. And with you.

Thank you, dear readers, from the bottom of my chocolate heart. Evan would have absolutely loved this.

“When the heart weeps for what it has lost, the spirit laughs for what it has found.”

~Sufi proverb