Côte d’Ivoire in Crisis – What Chocolate Lovers Can Do To Help

The current humanitarian situation in Côte d’Ivoire is dire. I’ve been watching from abroad since the fall of 2010, hunting down the occasional news article, radio broadcast, tweet, or YouTube video that has made its way into the American mediascape. At present, an estimated one million Ivorians have fled just from Abidjan, the country’s largest city and administrative center. Other citizens from all over the country find themselves similarly displaced; many have fled to neighboring Liberia as refugees. Since November 2010, fifteen hundred or more civilians have been killed as opposing military forces have battled.

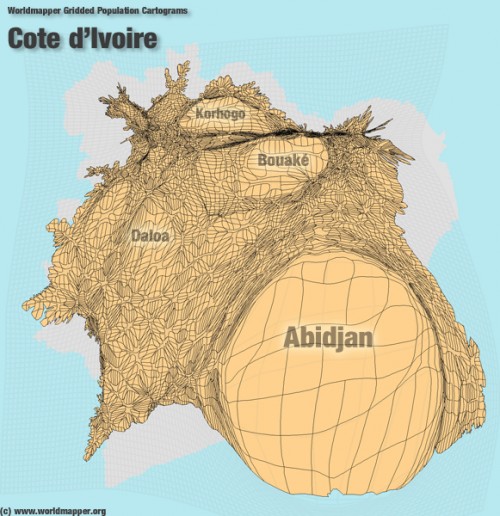

Côte d’Ivoire is Sub-Saharan Africa’s eighth largest economy and fourth largest exporter of goods and the world’s most prolific cocoa bean producer. Abidjan is second to only Nigeria’s Lagos in population in the region, making it the seventh largest city on the African continent. Its struggles are already creating ripple effects throughout the region and the international chocolate industry.

How did this happen?

In November 2010, incumbent president Laurent Gbagbo was voted out of office, losing to opponent Alassane Ouattara. The country of Côte d’Ivoire had long awaited these elections, which were repeatedly delayed by the Ivorian Civil War in the early 2000s. Idealists hoped that the elections would help to unify the country, which has long been divided ethnically, religiously, and geographically (north to south). The international community sanctioned the elections and proclaimed Ouattara the winner. The vote was close and tensions were very high. Gbagbo, who has held the presidency since 2000, refused to leave, however, contesting his loss.

From the outside, it is hard not to look on Gbagbo with contempt, given what has happened in his country since November. He has stubbornly remained in the presidential palace while chaos has descended outside; most recently he has hidden with his family in a luxurious basement bunker under the palace.

From the scant news, the outside world has learned that his troops have battled those of his opponent, shot down peacefully marching women, and killed hundreds of civilians. As Gbagbo has grown more desperate over these six months, he has threatened United Nations peacekeeping forces in the country, repeatedly rebuffed attempts to negotiate a peaceful resolution to the election aftermath, and worked to nationalize banks and the massive cocoa trading sector, frantically grasping for anything that might give him profit and power. He has long been an anti-colonialist, often xenophobic leader, which, the world’s hierarchy being as it is, has most certainly contributed to the international community’s general scorn for him and his policies. Following the election, he even went so far as to hire a famous US lobbyist to help him reform his image and argue for the legality of his retention of the presidency, though this eventually backfired.

But Gbagbo is not by any means hated by all Ivorians – he’s supported by a large number of them, in fact – a reported 46% of November’s voters chose him as their leader.

Opponent Alassane Ouattara is less vilified in the media and, as the international golden boy, makes a more sympathetic character to outsiders. For many years, his opponents have threatened him and his supporters, who have long played the underdog card in Ivorian politics. Yet Ouattara himself is powerful. He achieved success by hitching Côte d’Ivoire’s economy to France’s while working with the IMF and Central Bank of West African States and served as the unelected Prime Minister from 1990-1993. He is highly educated and an old friend of French leader Nicolas Sarkozy.

Since the election, Ouattara has remained in a hotel suite under the protection of UN peacekeepers. He has insisted, with the support of the international community, that he must be inaugurated as president. However, his troops, like Gbagbo’s, have also attacked, destroyed, and killed. They have been accused of massacring a village of several hundred civilians. And it is unclear that Ouattara, even with his wide and influential international network, could have peacefully unified the country had he begun his presidency as scheduled. Now, with the country’s stability so severely disrupted and his own credibility seriously marred, he will face even more enormous challenges once he is president.

International intervention (or lack thereof)

The African Union and ECOWAS have ousted Côte d’Ivoire from their ranks and repeatedly attempted to negotiate an exit for Gbagbo. They have imposed sanctions on the country in response to his resistance. Côte d’Ivoire’s neighbors – Liberia, Guinea, Mali, Burkina Faso, and Ghana – are ill equipped to assist with refugee camps for the many displaced Ivorians seeking safety and shelter. In fact, many citizens of these neighboring countries have long sought refuge in Côte d’Ivoire.

The United States has spoken out strongly against Gbagbo and in support of Ouattara, but actions have been limited to small-scale humanitarian donations and financial sanctions on Gbagbo and his wife. US Secretary of State Hillary Clinton has repeatedly called for Gbagbo to step down and issued statements against violence. President Obama has issued similar statements and recorded a video message to the people of Côte d’Ivoire, promising that those who choose democracy will have a friend and partner in the US.

Given the enormity of the humanitarian crisis in the country, though, these efforts seem nothing more than talk – the US has yet to take any substantive actions for the welfare of Côte d’Ivoire’s citizens. You can see many of the highlights of US State Department statements here.

Unfortunately, throughout the post-election chaos in Côte d’Ivoire, Americans have been preoccupied with numerous other news stories – developments in Egypt, Wisconsin, Japan, Libya, the US House budget proposal, and Rebecca Black’s viral music video “Friday.”

As time has passed, the US, EU, and UN Security Council have placed ever more stringent sanctions on Côte d’Ivoire. Sadly, these sanctions have made little difference to Gbagbo and enormous difference to the Ivorians who must survive in severely disrupted, precarious conditions. France, Côte d’Ivoire’s wealthy former colonizer, has only this week seized the country’s main airport and placed French nationals under their protection. Given France’s intense involvement in Côte d’Ivoire’s history and current economic standing, the lack of action on behalf of Ivorian citizens is deplorable.

As I write this blog post, talks between Gbagbo’s generals and the international community over a surrender have broken down once again. Ouattara’s forces stormed the presidential palace in early April, making their way closer to Gbagbo. Now UN peacekeeping and French forces are taking the offensive to physically remove him from the property. The EU has begun loosening sanctions against the cocoa sector in anticipation of Ouattara’s presidency. Still, the outcome remains uncertain. This fighting has gone on for many months, as has the inevitable human suffering that such events cause.

Why haven’t we heard more about this?

Perhaps most maddening to an outside observer is the lack of news about Côte d’Ivoire in major media outlets. The BBC and Voice of America give semi-regular updates, though articles are often terse and cold, reading like old-timey telegraphs. Other news articles are almost sickeningly inhuman, concentrating purely on the economic effects of the country’s instability. They list statistics, use obtuse trading jargon to explain the steep rise of cocoa prices, and describe sanctions – none of them tell much about what is happening on the ground. Will there be a chocolate drought?, headlines worry. Few headlines ask: Are the people in Côte d’Ivoire alright?

Nicholas Kristof, the two-time Pulitzer Prize winning New York Times journalist, is one of the few prominent journalists to take on the inequalities in reporting and intervention. In his April 3, 2011 column, “Is It Better to Save No One?”, he writes:

Critics argue that we are inconsistent, even hypocritical, in our military interventions. After all, we intervened promptly this time in a country with oil, while we have largely ignored Ivory Coast and Darfur – not to mention Yemen, Syria and Bahrain.

We may as well plead guilty. We are inconsistent. There’s no doubt that we cherry-pick our humanitarian interventions.

But just because we allowed Rwandans or Darfuris to be massacred, does it really follow that to be consistent we should allow Libyans to be massacred as well? Isn’t it better to inconsistently save some lives than to consistently save none?

He also updated his Facebook page to include this:

People often ask why there isn’t more coverage of Syria, Ivory Coast or Yemen. One answer is something that non-journalists sometimes don’t appreciate — the difficulty of getting visas. Yemen and Syria are completely blocking Americans. Only hope to get an Ivory Coast visa is to go to Senegal and beg its embassy there. Sad truth is we systematically undercover what we don’t get access to.

Even reading these quotes for the third, fourth time, I sigh. My mouth twists with frustration. Yes, Kristof has made very important points here, he has honestly confronted some sad truths in international relations and journalism. Photojournalist Jane Hahn has also vividly described the danger that journalists face in Côte d’Ivoire. The problem of difficulty in reporting is real, but does not provide an excuse for silence. Critical, informed commentary on this situation is essential and, especially thanks to social media, much can be done to overcome travel challenges.

Life is not easy, it is rarely just, we cannot help everyone all of the time. But the entire world of chocolate is implicated in Côte d’Ivoire’s troubles, and we must do better.

What does this have to do with chocolate?

Chances are if you are an American and have eaten candy in the past thirty years, you have consumed chocolate made from Côte d’Ivoire sourced cocoa beans.

Wikipedia best explains the massive presence of Côte d’Ivoire cocoa in the world:

Côte d’Ivoire (Ivory Coast) leads the world in production and export of the cocoa beans used in the manufacture of chocolate, supplying 46% of cocoa produced in the world. West Africa, collectively supplies nearly 70% of the world’s cocoa crop, with Côte d’Ivoire leading production at 1.3 million tons, followed by neighboring Ghana with 720 thousand tons. Côte d’Ivoire overtook Ghana as the world’s leading producer of cocoa beans in 1978. Large chocolate producers such as Cadbury, Hershey’s, and Nestle buy Ivorian cocoa futures and options through Euronext whereby world prices are set.

Persistent poverty and economic instability in Côte d’Ivoire are compounded by the consistently low prices paid to the more than one million cacao farmers by large multinational corporations. Inter-ethnic strife has been stirred up by the cocoa industry there; child slavery is a lasting problem. These issues are increasingly well-documented by researchers.

For an in-depth report, see the 2007 publication “Hot Chocolate – How Cocoa fuelled the conflict in Côte d’Ivoire,” prepared by Global Witness. For a shorter, but still informative article, see the April 25, 2011 edition of The Nation, “The Roots of the Côte d’Ivoire Crisis.”

Even knowing this information, large corporations continue to buy the largest proportion of cocoa beans in Côte d’Ivoire, with little effort toward labor reform and the implementation of fair trade practices. And we continue to eat the chocolate that results.

Our sweet tooths are partially responsible for this crisis and there are things that we can do to help the people of Côte d’Ivoire.

What can you do?

Contact US lawmakers: If you are based in the US, you can contact a number of different government representatives about the situation in Côte d’Ivoire. Let them know your opinions on the situation and encourage them to take action as your elected leaders. They are able to do numerous things; perhaps most urgent now is the provision of humanitarian aid for Côte d’Ivoire’s citizens.

- Senator John Kerry (MA) is the current Chairman of the US Senate Committee on Foreign Relations. His contact information is available here.

- The Senate Foreign Relations Subcommittee on African Affairs is made up of nine senators from all over the country. Their names and contact information are available here.

- The House of Representatives Committee on Foreign Affairs, Subcommittee on Africa, Global Health, and Human Rights is made up of eight representatives from all over the country. Their names and contact information are available here.

Donate to humanitarian organizations: If you are in the US or abroad and are willing and able to donate money to humanitarian organizations working in Côte d’Ivoire, there are several to choose from. These organizations are on the ground delivering services now, and donations will ensure that they can continue to do so.

- International Red Cross

- Oxfam

- UNHCR – the UN Refugee Agency

- UNICEF – the UN Children’s Fund

- World Food Programme

Contact chocolate companies and multinational corporations: If you are in the US or abroad and are a chocolate lover who hates what is happening in Côte d’Ivoire, contact some of the multinational multibillion dollar corporations that are purchasing chocolate there. Write to them, express your opinions, insist that they answer your questions.

These corporations include, but are not limited to, Hershey, Cargill, Archer Daniels Midland, and Barry Callebaut.

You can even write to these companies and tell them what you, as a consumer, think about their codes of ethical business conduct and corporate responsibility, which they display prominently on their websites.

- Hershey’s Code of Ethical Business Conduct

- Cargill’s Corporate Responsibility Reports

- ADM’s Corporate Responsibility Update

- Barry Callebaut’s Corporate Responsibility page

Get educated: Seek out more education on the chocolate that you eat and its impact on the lives of cacao farmers. Share what you learn with your family and friends. I am still learning myself and will continue to post here. You can also follow me on Twitter and Facebook, where I routinely update with chocolate news.

Many chocolate consumers express sticker shock about the cost of chocolate that is Fair Trade or otherwise produced with attention to fair labor practices. Quite frankly, we are cheapskates about the chocolate that we eat – it has been inexpensive for a long time because we have simply not paid cacao growers appropriately (or at all – cocoa production has a long history of slave labor). Are we not devaluing other people’s lives just to save a buck on our snacks?

Overwhelmed?

I highly recommend this perspective-granting essay written by Ivorian novelist Fatou Keïta, describing her life in Abidjan over the past several days.