Interview with Jeffrey Stern, Chocolatier and Chocolate Advocate in Quito, Ecuador, continued

Quito, Ecuador by Orban López Cruz

Jeffrey Stern is a chocolatier, chocolate advocate, entrepreneur, and blogger based in Quito, Ecuador. I recently asked Jeff to answer a long list of questions about his life and work, and he was kind enough to oblige. The first part of the interview can be read here. Below, in the second part of the interview, Jeff presents his views on standards in production, trade certifications, power relations, communication, and sharing in the chocolate world.

Fresh cacao by Mikko Koponen

Interview with Jeffrey Stern, Part 2, November 2011

Carla Martin (CDM): What standards in chocolate production do you value?

Jeffrey Stern (JM): I guess I’d have to say transparency over all. I’ll have to speak specifically to my situation in Ecuador on this first. I would love to be able to buy all chocolate made from pure Nacional beans for my production, but for both financial reasons and reasons of control, I can’t.

First off, the market here won’t bear a high cost chocolate. For example, I could buy Kallari couverture for all my chocolate making, but at $16 per kilo I’d lose money on everything I make. I just can’t pay that much for chocolate and be able to make money on it here. Unfortunately, we all have to eat.

Second, as I have discussed frequently, I can’t control what the local manufacturers’ choice of beans is and so I can’t know what beans they are using when they make chocolate. I wish I had large enough volume to have custom batches of chocolate made for my own use, but I don’t. So for local production, I buy some couverture at around $6 per kilo. If I had the volume, I’d source beans myself and have the chocolate made per my own specs. But what I buy at the lower end of the price scale is most likely mixed beans (CCN-51 and Nacional).

I do buy some pure Nacional couverture. How do I know it’s pure Nacional? I have a friend who is part owner in two large farms of pure Nacional cacao. I have been to the farms and seen them. He is Swiss, has lived here 30 years, I’ve been doing business with him nearly since I arrived five years ago, and I trust him. He has couverture made in country and sells it to me, among other people, at a fair price.

What’s important to me is to be able to know something, preferably a whole lot, about where my chocolate comes from, how it’s been produced, and what’s in it. I think the links most chocolate manufacturers state they have with the sources of their beans are tenuous at best most of the time, and certifications don’t really interest me as I don’t think they say much. It’s a paradox, but I would say the smaller, artisan chocolatiers are at both an advantage and disadvantage to the big guys. The big buyers can buy a whole farm or cooperative’s production and make a chocolate out of it and call it “Single Estate,” though that doesn’t mean it might not be mixed with other beans. But if they can’t get enough beans from one prime source, they are forced to blend. Economy of scale works both to their advantage and disadvantage. The small, artisan chocolatier can buy beans from just one or two or three prime sources, and can make a different batch of chocolate from each of those sources, which the big players can’t do because of scale problems.

I am not so much concerned with organic, Fair Trade, Rainforest Alliance, or other certifications. Here in Ecuador, to buy chocolate with any kind of certification is unfeasible price-wise for the local market. I think this is an interesting rhetorical question for consumers in the developed world to consider, too — “I can buy this ‘certified’ chocolate in the US, and yet there’s no market for it in the country of origin?” Right there is a topic to ponder.

CDM: How do you aim to share your knowledge about chocolate with others?

JS: I spend a lot of time online trying to blog, advocate, and discuss the issues facing Ecuadorian cacao, as well as many of the technical aspects of chocolate making, confectionery, etc. I don’t really focus on a global level as I don’t consider myself an expert on cacao worldwide — nor on cacao in general. But blogging only gets me so far and to a limited audience. I am hoping to get some video content online as well soon.

Fortunately, after four long and difficult years getting established in Ecuador and building a reputation as a person knowledgeable about chocolate and the industry here, I have been recognized and sought after by local businesses, especially in the travel and tourism area, and internationally. It’s unfortunate that I have to look mainly outside of Ecuador for interest in the ideas I have to share, but again, one has to make a living. I now have offerings with three different tour operators — I’ll be the guide for a four day portion of an eight day tour in February and March of 2012 with Ecuador Jungle Chocolate. The first four days will include visits to chocolate makers in Ecuador, and the second four will be focused on mushrooms with Larry Evans. I am also working with Quasar Nautica and Gentian Trails; we will have offerings of chocolate classes for tour groups, as well as tastings and visits to chocolate factories in Quito. I’ll also be meeting with and helping Sharon Lane as part of a documentary effort about chocolate in Ecuador in December 2011.

CDM: How do you communicate with other chocolate makers and chocolatiers?

JS: Most of the people I know in the chocolate community are extremely open and helpful. I use The Chocolate Life for some communication and information sharing and to help share some of my ideas. But I find my most valuable contacts are direct. Two years ago I had the opportunity to meet with Michael Recchiuti in San Francisco and spent a long Sunday morning with him, asking questions and sharing my experiences in Ecuador. Since then I’ve been fortunate enough to be able to email with him directly on many ocassions. I’ve also reached out to Christopher Elbow in Kansas City and he’s been very helpful. When I visit the US, which is almost every year, I try to take a class or two. Last year I took a class with Patrick Peeters, the head R&D Chef Chocolatier for North America at Godiva. Linkedin is also a great resource. I have been reaching out, expanding, and intensifying my efforts to stay connected with people in the US; even though I may be located in the “center” of the chocolate world in some ways, I often feel very much at the periphery of what’s going on in the world, because, let’s face it, the developed world where the money is drives the trends and shapes what happens with chocolate much more than the producers of cacao do.

I’ve also been extremely fortunate in working with Dana Brewster and Mark DelVecchio of Millcreek Cacao Roasters. They initially came to Ecuador to source cacao, hiring me as their guide. Since then, we’ve developed an excellent working relationship and we are working together on a Kickstarter project to be launched soon.

CDM: How do you understand your role or place in the chocolate world?

JS: My job as a chocolatier I wouldn’t replace for anything. While it’s totally unofficial, because chocolate is universally appreciated, I see myself as sort of an “Ambassador” for Ecuadorian chocolate and the issues surrounding it. Of course, many of the issues facing Ecuadorian cacao growers and the chocolate industry here have similar parallels elsewhere.

This summer I was at a cacao trader’s patio in El Empalme, Ecuador. He obviously moved large quantities of not only cacao, but also rice, coffee, and corn. I asked him if he exported and I was taken aback when he said no; he said he didn’t have the language ability nor the contacts to export. I think there are something like 36 official cacao exporters in Ecuador. Most of them don’t tell anyone much about what they’re doing, their business, or the issues involved. Maybe they’re too busy, they don’t want to, or they’re just not interested. There are also many cooperatives or producers’ associations in Ecuador — some do better than others at getting their stories out there. But in general, the small producer/cooperative/association is pretty much unknown. I would like to be able to remove the veil that covers the cacao trade at the ground level; too much of the business is controlled, both in economic terms and in “story” terms, by the big players and large markets.

I would love to see the day when consumers, through their pocketbooks, have influenced the other end of the cacao chain, especially the buyers, to pay a premium for pure Nacional cacao from Ecuador. A level playing field where Nacional is awarded a premium for its flavor profile and thus is once again more widely grown, despite its lower productivity and lower disease resistance than CCN-51, would be a boon for chocolate connoisseurs worldwide. It would be an amazing day if chocolate lovers worldwide would rise up in outrage like they recently have against Bank of America’s $5 debit card fees or Netflix’s plan changes! Sure, it’s not an exact parallel because these examples are about price hikes consumer don’t want; but if consumers were to respond in a similar fashion about price hikes they think farmers should get for their goods, well, this would be a radical shift in thinking.

CDM: How has travel and living abroad affected your appreciation and understanding of chocolate?

JS: I could never have learned all I know about Ecuadorian cacao and the industry here without having lived here for several years. I would never be able to understand the flavor nuances in chocolate without having tasted chocolate liquors from different farms. Now that I understand just how remote the source of much of the world’s great cacao is, it’s really amazing how it arrives all the way to your store or postbox. It arrives with such ease, and yet there is still such a large disconnect, and in academic speak, market fragmentation, on the ground here in Ecuador. The market mechanisms are broken and connections between cacao producers, cacao traders on the ground here, and cacao exporters are unregulated, unstandardized, and inefficient. This means that most of the time, small producers don’t get a fair price for their cacao, quality is not awarded the premiums it should get, and rare, fine aroma cacao doesn’t get the respect and treatment it deserves.

CDM: Is your fluency in Spanish important to your work?

JS: Without Spanish, which I learned by the way as an AFS Exchange Student to Chile in 1986, I would not be where I am today. Knowing Spanish allows me to communicate directly with everyone I work with, gives me additional business opportunities, and just opens an infinite number of doors to me as both an individual and a business person that weren’t even visible before. I of course use Spanish everyday, and it has allowed me to teach, share, and attract opportunities.

——————————————————————————————————————————–

Visit Jeffrey Stern’s blog here to learn more about his adventures with chocolate just south of the equator, and follow his company Gianduja Chocolate on his website and on Facebook. Also, stay tuned for Part 3 of this interview, as well as further details on Jeff’s upcoming Kickstarter campaign — he is currently working to launch a direct trade project to promote Ecuador’s heritage Nacional cacao and benefit small farmers.

Alexander and the Terrible, Horrible, No Good, Very Bad Halloween, by Jennifer Doody

Halloween by hanna horwath

The Halloween season often brings fond memories of tasty candy, fun costumes, and spooky nights. For author Jennifer Doody, it holds another significance altogether. In today’s guest post, Jennifer offers a tale of Halloween candy anguish and misfortune, an important reminder of the cultural differences that inform our tastes starting at a very young age.

————————————————————————————————————————–

Alexander and the Terrible, Horrible, No Good, Very Bad Halloween, by Jennifer Doody

Many years ago, my American family moved to Munich, Germany so my mother could pursue a career as an opera singer. My parents’ decision to not live on the nearby Army base was a deliberate one: as then-aspiring artists, progressives and intellectuals, they were determined that their four-year-old daughter would be immersed in this new and rich culture.

In the fall of my first year of school, my parents invited a boy from my German kindergarten class, Alexander Härting, to join us for Halloween. Back in the 1970s, cultural globalization wasn’t as widespread as it is now: aside from the Army bases, the only evidence of America’s presence was, of course, the golden arches of McDonald’s. Alexander had never heard of Halloween or the ritual of trick-or-treating, but his mother readily agreed, and once we threw together a standby cowboy costume for him, we were ready to go.

As Halloween wasn’t celebrated in Germany, we headed to the Army base to go door-to-door. At the first house, Alexander cautiously held out his bag, glancing over at me to make sure he was doing it right, and murmured a wary “Twick or tweet.” The woman smiled broadly and threw a huge candy bar into his bag, and another into mine. Alexander’s eyes, I remember, went as big as saucers: chocolate in Germany was much more of a special treat, something to be savored, and was often distributed in individual pieces. To have a six-ounce block of chocolate simply tossed into his waiting hands, not just once, but over and over, was the culinary equivalent of winning the World Cup.

Halloween Candy by slgckgc

When our bags sagged with sweet treasures, we returned to my parent’s apartment, where — in the finest American tradition — we dumped all our candy out onto my bed and tore into it greedily. Alexander grabbed the biggest candy bar of Hershey’s chocolate, tore off the wrapper, and bit into it with relish. He chewed joyfully, and then his face sagged, and he burst into tears.

It wasn’t his fault: he was used to German chocolate, of course. I munched pensively on my Snickers bar as he howled in outrage at the universe’s cruelty and betrayal. Shortly thereafter, his mother shamefacedly bundled him up and took him home, as no amount of cajoling or consolation could stop him from weeping. Thirty years later, it’s still the best visual image I have of instantaneous heartbreak and devastating disillusionment.

According to the Chocolate Museum in Cologne, as early as 1877, German chocolatiers set strict purity laws for their chocolate. The restrictions were meant to “protect their products from imitations and introduce binding quality restrictions.” In 1973, Germany was among the 50 countries to sign the first cocoa agreement, led by the International Cocoa and Chocolate Organisation (ICCO). America, the world’s greatest consumer of chocolate, declined.

Today, chocolate made in Germany must meet strict requirements for cocoa: 60% for dark chocolate, 50% for mild dark chocolate, 30% for whole milk chocolate, and 25% of milk chocolate (white chocolate — my personal favorite, although that’s another post! — is not required to contain cocoa mass at all, only cocoa butter). At the turn of the 20th century, Germany led all cocoa-consuming countries with “19,242 tonnes of processed cocoa beans… or 380 grams of cocoa beans were consumed per person annually.” In 2007, Germany ranked sixth in chocolate consumption, with each person in Germany eating 9.32 kg per year (the Irish were first, with each person in Ireland consuming 11.85 kg per year, followed by the Swiss, English, Belgians and Norwegians).

Every Halloween, I think of Alexander, and thank him for providing me with the best visual example of disillusion and despair –- not to mention the irrefutable realization that life is sometimes terribly, horribly, brutally unfair –- that I’ve ever witnessed. But I can’t blame him. To this day, when I’m traversing the streets of Boston and need a chocolate fix, I may make do with American chocolate in a pinch… but what I’m really craving is the creamy, “milk from the Alps” texture of Milka, or the rich diversity of Ritter Sport.

————————————————————————————————————————–

Jennifer Doody is a writer with 20 years experience in university news, communications, and academic editing, based in Boston, Massachusetts. Visit her professional site here to read more of her work.

Interview with Jeffrey Stern, chocolatier and chocolate advocate in Quito, Ecuador

Jeffrey Stern is a chocolatier, chocolate advocate, entrepreneur, and blogger based in Quito, Ecuador. I recently asked Jeff to answer a long list of questions about his life and work, and he was kind enough to oblige. Below, in the first half of this interview, Jeff details the missions of his companies and his educational and work background (which, I should note, left him singularly well prepared for his current work). He also explains many of the challenges that small batch production chocolatiers face in relation to direct trade, marketing, and domestic/international bureaucracy, as well as the travel and learning opportunities that forever changed the way he tastes and understands chocolate.

Photo courtesy of Jeffrey Stern

Interview with Jeffrey Stern, Part 1, October 2011

Carla Martin (CDM): What is the focus of your two companies, and what are their missions?

Jeffrey Stern (JS): The focus of my Ecuador based company, Gianduja Chocolate, is to provide high quality, sophisticated bonbons and chocolate products for the local market, using almost all local ingredients. I use only Ecuadorian chocolate, local fruits, cream, and butter, and the only imported items I use are those not available here like transfer sheets, real vanilla, and colored cocoa butters.

My other company, Aequare Fine Chocolates, had as its original mission the goal of importing, wholesaling, and retailing to the United States fine chocolates made in Ecuador with top quality Ecuadorian chocolate. Also, I made it a point of this company to have contact with and knowledge of the chocolate and its origins from bean to final product. I knew the grower of the beans and how he managed his farm, I knew the factory and operations where the chocolate was made, and of course I made the final chocolates myself. We imported into the United States and retailed through the website and worked with a few brokers. Ultimately, the idea was to add value to cacao in the country of origin, and have direct trade relationships with all our suppliers here in Ecuador.

Unfortunately, I think the story was somehow not compelling enough for consumers and what I envisioned as an artisan product being made in Ecuador simply ended up being perceived as another consumer packaged good once it was in the US. Sort of a “lost in translation” problem, as well as the difficulty of explaining a “direct trade” story when you don’t have a multimillion dollar marketing campaign behind the product(s), a big PR budget, etc.

Also, the lack of any US physical presence and someone who could do tastings and trade shows made it difficult to get the product exposure. I think if I had had a physical location somewhere that would have helped a lot. Finally, I see the whole marketing system in the US as such a giant machine, with brokers, distributors, etc. It’s really hard to get your product recognized and noticed, as well as costly if you want to do trade shows. Because the US market and system is so massive, I see it as causing an unfortunate disadvantage for the consumer who, despite the increasing growth and interest in artisan and handmade foods, remains highly disconnected from foods’ origins. And with chocolate, coming all the way from a far off country, it’s even harder to establish and tell a compelling story that offers the authenticity and traceability that consumers often want.

CDM: What are the primary activities of your chocolate and cacao education and training services?

JS: Primarily, I work with companies outside of Ecuador who usually know nothing about the country or the cocoa trade, and want to source either cacao from Ecuador or a semi-processed product such as cacao liquor or powder, or want to have a cacao-based product contract manufactured in Ecuador. I have also worked with artisan bean to bar companies who are looking to source cacao beans from Ecuador. Finally, I act as a “chocolate expert” for chocolate tours — these can be either groups who just have a casual interest in chocolate, or professional groups. I am currently working with three tour operators in Ecuador offering 3-5 day tours centered around chocolate activities, including visits to artisan chocolate makers, visits to plantations, fermentation and drying centers, brokers, and chocolate tastings. I have also been hired to work as a chocolate expert for a well known online chocolate school which will be offering a professional tour in June of next year for chocolatiers and bean to bar chocolate makers.

CDM: How were your companies started?

JS: I moved to Ecuador with my wife and family in May of 2007, with the intention of opening my chocolate business. I had lived in Ecuador from 1994 to 1995, first while getting my Master’s in Community and Regional Planning, and then returned to work for USAID after graduating. I then traveled to Ecuador almost annually until 2007. I got the idea of starting the chocolate business several years after I changed careers (2001, when I attended culinary school). We did some test marketing in trips to Ecuador in 2005 and 2006, and found there was a good market for chocolate. I founded my other company, Aequare, in 2008, with the intention of exporting chocolates from Ecuador. After our first year here, I realized the market wasn’t as big as I had initially expected, and decided to export.

CDM: How are your companies structured, and how many employees work with the companies?

JS: Our local company in Ecuador, Gianduja Chocolate, is a sole proprietorship. I am the chocolatier, my wife takes care of administration and accounting, and I have one employee who knows about 80% of what I do. My other company is an LLC. I am the only employee. When the need arises, I occasionally hire an additional person, but due to very onerous labor laws in Ecuador which make part-time or hourly payment nearly impossible, it’s rare.

CDM: What is your educational background and training?

JS: I have a Bachelor’s in Latin American Studies from New York University and a Master’s Degree in Community and Regional Planning from the University of Texas at Austin. I am also a 2001 graduate of L’Academie de Cuisine in Gaithersburg, Maryland, where I earned a degree in culinary arts.

CDM: What type of work were you involved in before beginning these companies? Was it related to or unrelated to chocolate?

JS: My first career after college and graduate school was primarily in foreign aid; specifically, I spent several years working with USAID based in Ecuador. I also worked with a consulting firm in Washington, DC for one year that was focused primarily on World Bank, Inter-American Development Bank, and USAID projects. I spent two years in Nicaragua working in population and health programs with USAID as well. None of the work was related to chocolate.

After completing my culinary training, I worked in restaurants, catering operations, and as a personal chef. I later worked in a chocolate shop part-time.

CDM: What are some of the challenges that you have encountered while running your businesses?

JS: Ecuador’s environment, both on the private sector side and the public (government) side is all about friction. There seems to be a genuine lack of cooperation — it sounds amusing, but it’s not.

While getting permits and paperwork for operating has gotten a little bit more transparent in recent years, things still seem very arbitrary and ambiguous. It used to be that you had to hire an “expediter” to get almost anything done — that’s doublespeak for someone who you pay to grease the wheels of bureaucracy and issue you permits in a timely fashion. Now you can get many permits directly yourself, but the amount of time and money involved makes it just as costly as if you had hired the expediter.

When you go to an agency, be it the Municipality, the tax agency, the Ministry of Health, you can get one answer one day, and the next day you go back with the same question, and you’ll get an entirely different answer. You get the feeling that nobody really knows the rules, and that they’re being made up as things move along. So you never are really sure if you’re doing things right. It’s very frustrating and unnerving.

On the private sector side, there are difficulties in getting paid. No one uses the mail here, and messenger services only occasionally. Electronic payments are the exception, not the rule. Most companies pay from 2pm-4pm on Friday afternoons at their offices. So if you can’t make it to pick up your check, you have to wait another week to get paid. Fortunately, I have enough business now and a unique product that allows me to have a “cash only — take it or leave it” policy. That is, if you want the product, it’s cash or check on delivery, with few exceptions only for longstanding clients.

There’s very little collaboration or cooperation among similar types of businesses to help each other out. For example, there is no organization or association in Quito of chocolate makers who might attempt to work together for publicity or other ends to grow the market cooperatively for their products. Businesses jealously guard their secrets. I call this an economy of scarcity, not abundance, and thus, because even information is scarce, no one shares it. I think in the long run it’s detrimental to business, and while this is a broad generalization, I think the lack of trust and cooperation is one of the factors that hinders economic growth.

CDM: How do you keep up to date with new developments in chocolate?

JS: I mostly use the web to learn about what is going on in the chocolate world. Here in Ecuador, I have regular contact with people in the cacao and chocolate industry from growers to manufacturers of chocolate and semi-processed products such as liquor and powder. We have recently formed a group of professsional industry people involved in chocolate at all points in the supply chain called the “Academia de Chocolate,” which is another forum for sharing and gathering information.

CDM: Why chocolate? What about it is fascinating to you?

JS: I got interested in chocolate when I started working part-time in a chocolate shop. I hadn’t really gotten a good understanding of how to work with chocolate in culinary school, so I got some books and started to study on my own. There are very few sources that clearly explain what tempering chocolate actually is; when I was finally able to read about the polymorphism of cocoa butter and how temperature affects crystal formation in chocolate, I was able to wrap my head around it. Not only does chocolate taste good, of course, but it’s a fascinating substance to work with.

After almost 5 years in Ecuador in the chocolate business, my knowledge has expanded far beyond just the technical know-how of chocolate making. I have knowledge of bean to bar operations, identifying quality cacao, import/export operations, and how the cacao industry works in Ecuador.

CDM: What was your “aha” moment in relation to chocolate?

JS: I never really understood what chocolate was and how its flavor was developed until I actually went to a plantation and tasted several chocolate liquors (pastes) made on the spot from beans. When I tasted various liquors side by side from beans from different areas, with different fermentation, I suddenly realized just how important the beans are and just how different beans with different fermentations, roasts, etc can be. It was like a light bulb went on in my head — a total epiphany. Now when I taste chocolate I have a much better picture in my head (or taste map, however you’d call it) of what’s good or off about a chocolate’s flavor than I ever did before.

——————————————————————————————————————————–

Visit Jeffrey Stern’s blog here to learn more about his adventures with chocolate just south of the equator, and follow his company Gianduja Chocolate on his website and on Facebook. Also, stay tuned for Part 2 of this interview, as well as details on Jeff’s upcoming Kickstarter campaign — he is currently working to launch a direct trade project to promote Ecuador’s heritage Nacional cacao and benefit small farmers.

Update (November 8, 2011): Part 2 of the interview can be read here.

Chocolate travel: Black Dinah Chocolatiers, Isle au Haut, Maine

High on the American eastern seaboard lies an island blanketed by tall pine trees and edged with rocky coast line — Isle au Haut. The island is 12.7 miles square, with a year round community of approximately 80, mostly working in the lobster fishing industry. Large portions of the land are designated as Acadia National Park. This protected beauty attracts seasonal vacationers and tourists; the population nearly doubles in the summer.

On a recent summer Sunday, I joined my mother, aunt, uncle, and two close family friends on a mailboat ride from the mainland to Isle au Haut. Our mission? To eat chocolate.

Here is our story as I remember it.

Our journey began early in the morning at the mailboat ticket office in Stonington, Maine. Riders stacked their belongings in line to ensure a space on the boat.

Sisters embraced and smiled on the dock.

The fine vessel, Miss Lizzie, waited patiently to escort her passengers across the sea.

Once aboard, we bid the small town a temporary goodbye.

We sighted a pirate ship on the horizon and were suddenly grateful for having left our treasures at home.

Postcard picturesque Stonington quietly watched us depart.

The mainland disappeared. Dark forested islands and blue sky welcomed us.

An hour later, we landed at Isle au Haut. “You’re almost there!” encouraged a weather weary note.

We walked along a sunny, tree lined road until we saw this sign.

And there, nestled amongst the sweet smelling pines

was a home, with a small cafe at its side.

Inside, we found a case filled with chocolate and topped with plates of buttery pastries.

a sweaty glass of iced sipping chocolate,

and a delightful, tasty bonbon.

In truth, there were several delightful, tasty bonbons.

Behind the cafe, we saw a shiny new commercial kitchen with solar roof panels.

Then we hiked several miles through the forest,

where we were spotted by a deer

not far from a babbling brook.

covered with rocks, shells, and driftwood,

and admired coastal Maine object collage.

We basked in the warmth of good company.

Eventually we reached the end of the island

and the faithful Miss Lizzie came to spirit us away.

At sea again, we passed rocky islets home to birds and seals,

and stopped at barnacled docks where the boat gently dipped and swayed in the water.

The world glinted and sparkled. A porpoise dove playfully at our side.

Wispy clouds waved farewell. And I thought, “This is the way life should be.”

Sometimes chocolate is as much about the experience as it is about the taste.

To learn more about Black Dinah Chocolatiers, see this article from the Boston Globe and visit the company’s website. The Farm Market Collection, truffles made with local Maine ingredients, is extra special. You can also pre-order the Black Dinah Chocolatiers upcoming cookbook Desserted: Recipes and Tales from an Island Chocolatier. I am grateful to Kate and Steve, the owners, for so kindly welcoming us into their cafe and home and for feeding us such lovely treats. And to my wonderful Isle au Haut travel companions, many happy thanks for the scrumptious memories.

Wacky World of Choc Wednesdays: Harry Potter’s chocolate habit

“Chocolate. Eat. It’ll help.”

~Remus Lupin to Harry Potter, Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban

The interwebs are all abuzz for Harry Potter, and rightly so, in celebration of the release of the last film installment. For lovers of the books and films alike, this is a very exciting, although bittersweet time.

All the more appropriate, then, to consider the importance of chocolate in the wizarding world. Its comforting properties for emotional fans are most welcome now.

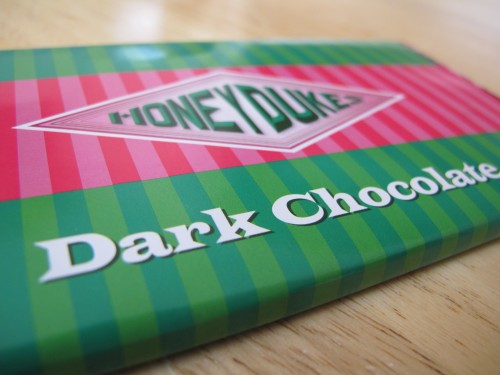

Not long ago, a delightful friend visited the Wizarding World of Harry Potter, a new theme park at Universal Orlando. When I saw her soon after, she generously presented me with this special token – the Honeydukes Dark Chocolate bar.

Of course I can’t eat it yet. It’s too special. I need to stare at it and desire it for a long time first. Or save it for use in the event of a Dementor attack.

The gift of this bar and my friend’s contagious enthusiasm for Harry Potter rekindled my curiosity and got me sniffing around for chocolate’s place in the Harry Potter stories. As it turns out, those wonderful wizards just might be a bunch of chocoholics like us Muggles (or Muggle-born, as the case might be).

According to the Harry Potter Wiki:

Chocolate has special properties in the wizarding world.

Not only does it make a wonderful treat for the consumer, but it serves as a powerful and excellent antidote for the chilling, cold effect produced by contact with Dementors, and other particularly nasty forms of dark magic. Remus Lupin carried chocolate with him on the Hogwarts Express and gave Harry Potter some after the latter was attacked by a Dementor. When Madam Pomfrey heard that Remus Lupin had given Harry chocolate after his encounter with the Dementor, she nodded approvingly and stated that “at last, we have a Defence Against the Dark Arts teacher who knows his remedies.” She herself used a large chunk of Honeydukes chocolate in the hospital wing to treat Harry Potter and Hermione Granger after they and Sirius Black were attacked by several Dementors in 1994.

Throughout the books, Harry and his fellow wizards stock up on treats at the beloved Honeydukes, a sweet shop in picturesque, magical Hogsmeade Village. (Like all excellent candy shops, its basement hides a secrete passageway to Hogwarts.) References to all manner of candy, much of it chocolatey, abound. There’s Charm Choc, Chocoballs, Chocolate Cauldrons, Chocolate Frogs, Chocolate Skeletons, Chocolate Wands, Choco-Loco, exploding bonbons (which contain pure cocoa and coconut dynamite!), Fudge Flies, Shock-o-Choc, and Wizochoc, just to name a few. The Harry Potter Wiki provides a comprehensive list.

But where do we, the humble, hungry fans, find chocolate suitable for a wizard’s cravings and/or antidotal needs?

We’re in luck, thanks to the Wizarding World’s Honeydukes Homemade Sweets shop, which now has a US location and countrywide distribution of a line of Harry Potter tie-in candies that are actually available in real life.

Universal describes Honeydukes as:

A must-stop for visitors to Hogsmeade, at Honeydukes the shelves are lined with all manner of colorful sweets, including Acid Pops, exploding bonbons, Cauldron Cakes, treacle fudge, Fizzing Whizzbees, and Chocolate Frogs, which contain a wizard training card in each box. Inside the shop you can fill up a bag of Bertie Bott’s Every-Flavour Beans… who knows what tasty (or not so tasty) flavors you’ll discover! The shop also offers other classic favorites such as chocolates and fudge.

Here’s a video showing the theme park location of the sweets shop:

I find myself happily caught up in the Harry Potter frenzy. I even watched the sappy J.K. Rowling docudrama (Magic Beyond Words: The J.K. Rowling Story, starring Poppy Montgomery) on Lifetime — it was cloyingly adorable. In doing this research on chocolate, I’ve decided that there are several wizard candies that I’d like to try. They are: the Honeydukes milk chocolate bar, Chocolate Frogs, Bertie Bott’s Jelly Beans (so eww but so cool!), Fudge Flies, Droobles Best Blowing Gum, Jelly Slugs, Acid Pops, and Fizzing Whizbees.

Oh, who am I kidding, I’d like to try them all. And I plan to.

“After all, it does not do to dwell on dreams and forget to live, remember that.” (wisdom from Albus Dumbledore, quoted in Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone)

A note on the ethics behind this line of candy: The company that produces Harry Potter chocolate received a failing grade from the International Labor Rights Forum. Members of The Harry Potter Alliance, a non-profit organization devoted to civic engagement using parallels from the Harry Potter books, have recently made great strides in asking Warner Bros. to choose fair trade chocolate for its candy products. Actors from the film series have also joined in this active campaign. See this Child Slavery Horcrux Update for more information. I plan to get involved immediately and I am hopeful that this continued advocacy and intervention will make a difference.